|

|

Популярные авторы:: Раззаков Федор :: Горький Максим :: Грин Александр :: Борхес Хорхе Луис :: Азимов Айзек :: Лесков Николай Семёнович :: Толстой Лев Николаевич :: Чехов Антон Павлович :: Кларк Артур Чарльз :: Картленд Барбара Популярные книги:: Дюна (Книги 1-3) :: Справочник по реестру Windows XP :: Паштет из гусиной печенки :: Цена риска [Риск] :: Мнимые величины :: Жизнь Клима Самгина (Часть 4) :: Краткое содержание произведений русской литературы I половины XX века :: An Encounter :: The Boarding House :: Летняя ночь |

True NamesModernLib.Net / Научная фантастика / Vinge Vernor / True Names - Чтение (стр. 6)

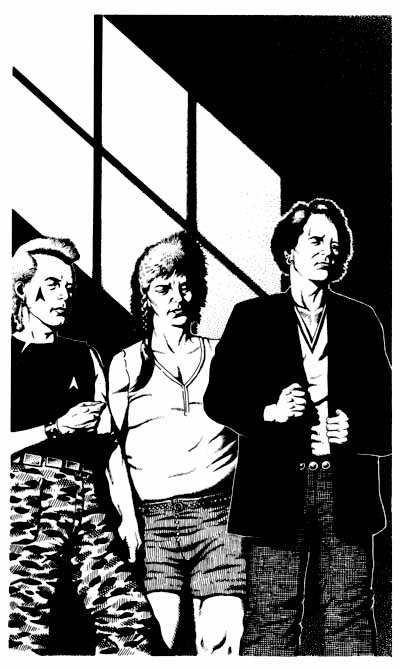

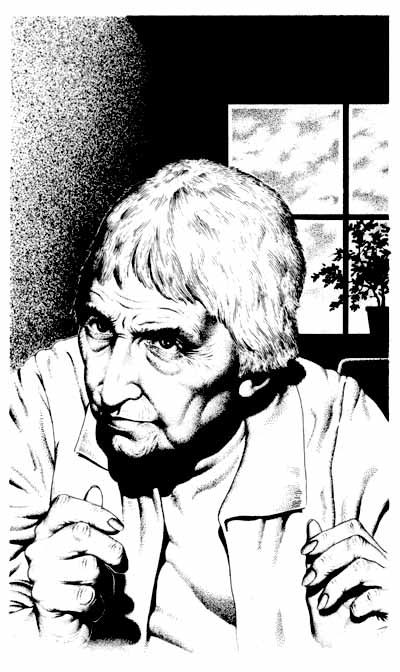

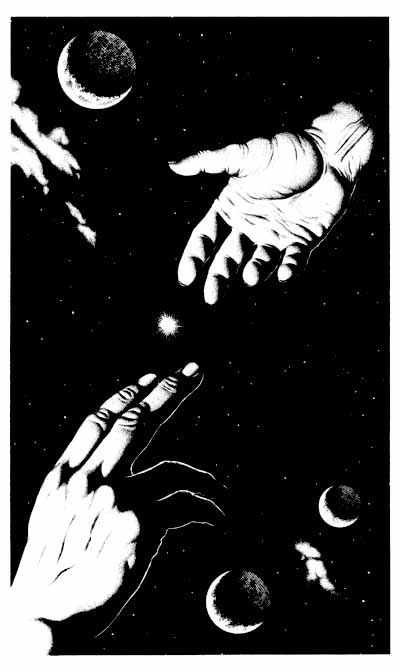

But when he reached it, he found floor 28 no different from the others he had seen: carpeted hall-way stretching away forever beneath dim lights that showed identical module doorways dwindling in perspective. What was Debbie/Erythrina like that she would choose to live here? "Hold it." Three teenagers stepped from behind the slant of the stairs. Pollack's hand edged toward his coat pocket. He had heard of the gangs. These three looked like heavies, but they were well and conservatively dressed, and the small one actually had his hair in a braid. They wanted very much to be thought part of the establishment.  The short one flashed something silver at him. "Building Police." And Pollack remembered the news stories about Federal Urban Support paying youngsters for urbapt security: "A project that saves money and staff, while at the same time giving our urban youth an opportunity for responsible citizenship." Pollack swallowed. Best to treat them like real cops. He showed them his id. "I'm from out of state. I'm just visiting." The other two closed in, and the short one laughed. "That's sure. Fact, Mr. Pollack, Sammy's little gadget says you're in violation of Building Ordinance." The one on Pollack's left waved a faintly buzzing cylinder across Pollack's jacket, then pushed a hand into the jacket and withdrew Pollack's pistol, a lightweight ceramic slug — gun perfect for hunting hikes — and which should have been perfect for getting past a building's weapon detectors. Sammy smiled down at the weapon, and the short one continued, "Thing you didn't know, Mr. Pollack, is Federal law requires a metal tag in the butt of these cram guns. Makes 'em easy to detect." Until the tag was removed. Pollack suspected that somehow this incident might never be reported. The three stepped back, leaving the way clear for Pollack. "That's all? I can go?" The young cop grinned. "Sure. You're out-of-towner. How could you know?" Pollack continued down the hall. The others did not follow. Pollack was fleetingly surprised: maybe the FUS project actually worked. Before the turn of the century, goons like those three would have at least robbed him. Instead they behaved something like real cops. Or maybe — and he almost stumbled at this new thought — they all work for Ery now . That might be the first symptom of conquest: the new god would simply become the government. And he — the last threat to the new order — was being granted one last audience with the victor. Pollack straightened and walked on more quickly. There was no turning back now, and he was damned if he would show any more fear. Besides, he thought with a sudden surge of relief, it was out of his control now. If Ery was a monster, there was nothing he could do about it; he would not have to try to kill her. If she were not, then his own survival would be proof, and he need think of no complicated tests of her innocence. He was almost hurrying now. He had always wanted to know what the human being beyond Erythrina was like; sooner or later he would have had to do this anyway. Weeks ago he had looked through all the official directories for the state of Rhode Island, but there wasn't much to find: Linda and Deborah Charteris lived at 28355 Place on 4448 Grosvenor Row. The public directory didn't even show their "interests and occupations." 28313, 315, 317 …. His mind had gone in circles, generating all the things Debby Charteris might turn out to be. She would not be the exotic beauty she projected in the Other Plane. That was too much to hope for; but the other possibilities vied in his mind. He had lived with each, trying to believe that he could accept whatever turned out to be the case: Most likely, she was a perfectly ordinary looking person who lived in an urbapt to save enough money to buy high-quality processing equipment and rent dense comm lines. Maybe she wasn't good-looking, and that was why the directory listing was relatively secretive. Almost as likely, she was massively handicapped. He had seen that fairly often among the warlocks whose True Names he knew. They had extra medical welfare and used all their free money for equipment that worked around whatever their problem might be — paraplegia, quadriplegia, multiple sense loss. As such, they were perfectly competitive on the job market, yet old prejudices often kept them out of normal society. Many of these types retreated into the Other Plane, where one could completely control one's appearance. And then, since the beginning of time, there had been the people who simply did not like reality, who wanted another world, and if given half a chance would live there forever. Pollack suspected that some of the best warlocks might be of this type. Such people were content to live in an urbapt, to spend all their money on processing and life-support equipment, to spend days at a time in the Other Plane, never moving, never exercising their real world bodies. They grew more and more adept, more and more knowledgeable — while their bodies slowly wasted. Pollack could imagine such a person becoming an evil thing and taking over the Mailman's role. It would be like a spider sitting in its web, its victims all humanity. He remembered Ery's contemptuous attitude on learning he never used drugs to maintain concentration and so stay longer in the Other Plane. He shuddered. And there, finally, and yet too soon, the numbers 28355 stood on the wall before him, the faint hall light glistening off their bronze finish. For a long moment, he balanced between the fear and the wish. Finally he reached forward and tapped the door buzzer. Fifteen seconds passed. There was no one nearby in the hall. From the corner of his eye, he could see the "cops" lounging by the stairs. About a hundred meters the other way, an argument was going on. The contenders rounded the faraway corner and their voices quieted, leaving him in near silence. There was a click, and a small section of the door became transparent, a window (more likely a holo) on the interior of the apt. And the person beyond that view would be either Deborah or Linda Charteris. "Yes?" The voice was faint, cracking with age. Pollack saw a woman barely tall enough to come up to the pickup on the other side. Her hair was white, visibly thin on top, especially from the angle he was viewing. "I'm… I'm looking for Deborah Charteris." "My granddaughter. She's out shopping. Down-stairs in the mall, I think." The head bobbed, a faintly distracted nod. "Oh. Can you tell me — " Deborah, Debby. It suddenly struck him what an old-fashioned name that was, more the name of a grandmother than a granddaughter. He took a quick step to the door and looked down through the pane so that he could see most of the other's body. The woman wore an old-fashioned skirt and blouse combination of some brilliant red material. Pollack pushed his hand against the immovable plastic of the door. "Ery, please. Let me in." The pane blanked as he spoke, but after a moment the door slowly opened. "Okay." Her voice was tired, defeated. Not the voice of a god boasting victory. The interior was decorated cheaply and with what might have been good taste except for the garish excesses of red on red. Pollack remembered reading somewhere that as you age, color sensitivity decreases. This room might seem only mildly bright to the person Erythrina had turned out to be. The woman walked slowly across the tiny apt and gestured for him to sit. She was frail, her back curved in a permanent stoop, her every step considered yet tremulous. Under the apt's window, he noticed an elaborate GE processor system. Pollack sat and found himself looking slightly upward into her face.  "Slip — or maybe I should call you Roger here-you always were a bit of a romantic fool." She paused for breath, or perhaps her mind wandered. "I was beginning to think you had more sense than to come out here, that you could leave well enough alone." "You … you mean, you didn't know I was coming?" The knowledge was a great loosening in his chest. "Not until you were in the building." She turned and sat carefully upon the sofa. "I had to see who you really are," and that was certainly the truth. "After this spring, there is no one the likes of us in the whole world." Her face cracked in a little smile. "And now you see how different we are. I had hoped you never would and that someday they would let us back together on the Other Plane…. But in the end, it doesn't really matter." She paused, brushed at her temple, and frowned as though forgetting something, or remembering something else. "I never did look much like the Erythrina you know. I was never tall, of course, and my hair was never red. But I didn't spend my whole life selling life insurance in Peoria, like poor Wiley." "You… you must go all the way back to the beginning of computing." She smiled again, and nodded just so, a mannerism Pollack had often seen on the Other Plane."Almost, almost. Out of high school, I was a keypunch operator. You know what a keypunch is?" He nodded hesitantly, visions of some sort of machine press in his mind. "It was a dead — end job, and in those days they'd keep you in it forever if you didn't get out under your own power. I got out of it and into college quick as I could, but at least I can say I was in the business during the stone age. After college, I never looked back; there was always so much happening. In the Nasty Nineties, I was on the design of the ABM and FoG control programs. The whole team, the whole of DoD for that matter, was trying to program the thing with procedural languages; it would take 'em a thousand years and a couple of wars to do it that way, and they were beginning to realize as much. I was responsible for getting them away from CRTs, for getting into really interactive EEG programming — what they call portal programming nowadays. Sometimes … sometimes when my ego needs a little help, I like to think that if I had never been born, hundreds of millions more would have died back then, and our cities would be glassy ponds today. "… And along the way there was a marriage …" her voice trailed off again, and she sat smiling at memories Pollack could not see. He looked around the apt. Except for the processor and a fairly complete kitchenette, there was no special luxury. What money she had must go into her equipment, and perhaps in getting a room with a real exterior view. Beyond the rising towers of the Grosvenor complex, he could see the nest of comm towers that had been their last-second salvation that spring. When he looked back at her, he saw that she was watching him with an intent and faintly amused expression that was very familiar. "I'll bet you wonder how anyone so daydreamy could be the Erythrina you knew in the Other Plane." "Why, no," he lied. "You seem perfectly lucid to me." "Lucid, yes. I am still that, thank God. But I know — and no one has to tell me — that I can't support a train of thought like I could before. These last two or three years, I've found that my mind can wander, can drop into reminiscence, at the most inconvenient times. I've had one stroke, and about all 'the miracles of modern medicine' can do for me is predict that it will not be the last one. "But in the Other Plane, I can compensate. It's easy for the EEG to detect failure of attention. I've written a package that keeps a thirty-second backup; when distraction is detected, it forces attention and reloads my short-term memory. Most of the time, this gives me better concentration than I've ever had in my life. And when there is a really serious wandering of attention, the package can interpolate for a number of seconds. You may have noticed that, though perhaps you mistook it for poor communications coordination." She reached a thin, blue-veined hand toward him. He took it in his own. It felt so light and dry, but it returned his squeeze. "It really is me — Ery — inside, Slip." He nodded, feeling a lump in his throat. "When I was a kid, there was this song, something about us all being aging children. And it's so very, very true. Inside I still feel like a youngster. But on this plane, no one else can see…" "But I know, Ery. We knew each other on the Other Plane, and I know what you truly are. Both of us are so much more there than we could ever be here." This was all true: even with the restrictions they put on him now, he had a hard time understanding all he did on the Other Plane. What he had become since the spring was a fuzzy dream to him when he was down in the physical world. Sometimes he felt like a fish trying to imagine what a man in an airplane might be feeling. He never spoke of it like this to Virginia and her friends: they would be sure he had finally gone crazy. It was far beyond what he had known as a warlock. And what they had been those brief minutes last spring had been equally far beyond that. "Yes, I think you do know me, Slip. And we'll be … friends as long as this body lasts. And when I'm gone — " "I'll remember; I'll always remember you, Ery." She smiled and squeezed his hand again. "Thanks. But that's not what I was getting at…. " Her gaze drifted off again. "I figured out who the Mailman was and I wanted to tell you." Pollack could imagine Virginia and the other DoW eavesdroppers hunkering down to their spy equipment. "I hoped you knew something." He went on to tell her about the Slimey Limey's detection of Mailman — like operations still on the System. He spoke carefully, knowing that he had two audiences. Ery — even now he couldn't think of her as Debby — nodded. "I've been watching the Coven. They've grown, these last months. I think they take themselves more seriously now. In the old days, they never would have noticed what the Limey warned you about. But it's not the Mailman he saw, Slip." "How can you be sure, Ery? We never killed more than his service programs and his simulators-like DON.MAC. We never found his True Name. We don't even know if he's human or some science-fictional alien." "You're wrong, Slip. I know what the Limey saw, and I know who the Mailman is — or was," she spoke quietly, but with certainty. "It turns out the Mailman was the greatest cliche of the Computer Age, maybe of the entire Age of Science." "Huh?" "You've seen plenty of personality simulators in the Other Plane. DON.MAC — at least as he was rewritten by the Mailman — was good enough to fool normal warlocks. Even Alan, the Coven's elemental, shows plenty of human emotion and cunning." Pollack thought of the new Alan, so ferocious and intimidating. The Turing T-shirt was beneath his dignity now. "Even so, Slip, I don't think you've ever believed you could be permanently fooled by a simulation, have you?" "Wait. Are you trying to tell me that the Mailman was just another simulator? That the time lag was just to obscure the fact that he was a simulator? That's ridiculous. You know his powers were more than human, almost as great as ours became." "But do you think you could ever be fooled?" "Frankly, no. If you talk to one of those things long enough, they display a repetitiveness, an inflexibility that's a giveaway. I don't know; maybe someday there'll be programs that can pass the Turing test. But whatever it is that makes a person a person is terribly complicated. Simulation is the wrong way to get at it, because being a person is more than symptoms. A program that was a person would use enormous data bases, and if the processors running it were the sort we have now, you certainly couldn't expect real-time interaction with the outside world." And Pollack suddenly had a glimmer of what she was thinking. "That's the critical point, Slip: if you want real-time interaction . But the Mailman — the sentient, conversational part — never did operate real time. We thought the lag was a communications delay that showed the operator was off-planet, but really he was here all the time. It just took him hours of processing time to sustain seconds of self-awareness." Pollack opened his mouth, but nothing came out. It went against all his intuition, almost against what religion he had, but it might just barely be possible. The Mailman had controlled immense resources. All his quick time reactions could have been the work of ordinary programs and simulators like DON.MAC. The only evidence they had for his humanity were those teleprinter conversations where his responses were spread over hours. "Okay, for the sake of argument, let's say it's possible. Someone, somewhere had to write the original Mailman. Who was that?" "Who would you guess? The government, of course. About ten years ago. It was an NSA team trying to automate system protection. Some brilliant people, but they could never really get it off the ground. They wrote a developmental kernel that by itself was not especially effective or aware. It was designed to live within large systems and gradually grow in power and awareness, independent of what policies or mistakes the operators of the system might make. "The program managers saw the Frankenstein analogy — or at least they saw a threat to their personal power — and quashed the project. In any case, it was very expensive. The program executed slowly and gobbled incredible data space." "And you're saying that someone conveniently left a copy running all unknown?" She seemed to miss the sarcasm. "It's not that unlikely. Research types are fairly careless-outside of their immediate focus. When I was in FoG, we lost thousands of megabytes 'between the cracks' of our data bases. And back then, that was a lot of memory. The development kernel is not very large. My guess is a copy was left in the system. Remember, the kernel was designed to live untended if it ever started executing. Over the years it slowly grew — both be — cause of its natural tendencies and because of the increased power of the nets it lived in." Pollack sat back on the sofa. Her voice was tiny and frail, so unlike the warm, rich tones he remembered from the Other Plane. But she spoke with the same authority. Debby's — Erythrina's — pale eyes stared off beyond the walls of the apt, dreaming. "You know, they are right to be afraid," she said finally. "Their world is ending. Even without us, there would still be the Limey, the Coven — and someday most of the human race." Damn. Pollack was momentarily tongue-tied, trying desperately to think of something to mollify the threat implicit in Ery's words. Doesn't she understand that DoW would never let us talk unbugged? Doesn't she know how trigger-happy scared the top Feds must be by now? But before he could say anything, Ery glanced at him, saw the consternation in his face, and smiled. The tiny hand patted his. "Don't worry, Slip. The Feds are listening, but what they're hearing is tearful chitchat — you overcome to find me what I am, and me trying to console the both of us. They will never know what I really tell you here. They will never know about the gun the local boys took off you." "What?" "You see, I lied a little. I know why you really came. I know you thought that I might be the new monster. But I don't want to lie to you anymore. You risked your life to find out the truth, when you could have just told the Feds what you guessed." She went on, taking advantage of his stupefied silence. "Did you ever wonder what I did in those last minutes this spring, after we surrendered — when I lagged behind you in the Other Plane? "It's true, we really did destroy the Mailman; that's what all that unintelligible data space we plowed up was. I'm sure there are copies of the kernel hidden here and there, like little cancers in the System, but we can control them one by one as they appear. "I guessed what had happened when I saw all that space, and I had plenty of time to study what was left, even to trace back to the original research project. Poor little Mailman, like the monsters of fiction he was only doing what he had been designed to do. He was taking over the System, protecting it from everyone — even its owners. I suspect he would have announced himself in the end and used some sort of nuclear blackmail to bring the rest of the world into line. But even though his programs had been running for several years, he had only had fifteen or twenty hours of human type self-awareness when we did him in. His personality programs were that slow. He never attained the level of consciousness you and I had on the System. "But he really was self-aware, and that was the triumph of it all. And in those few minutes, I figured out how I could adapt the basic kernel to accept any input personality. … That is what I really wanted to tell you." "Then what the Limey saw was — " She nodded. "Me …" She was grinning now, an open though conspiratorial grin that was very familiar. "When Bertrand Russell was very old, and probably as dotty as I am now, he talked of spreading his interests and attention out to the greater world and away from his own body, so that when that body died he would scarcely notice it, his whole consciousness would be so diluted through the outside world. "For him, it was wishful thinking, of course. But not for me. My kernel is out there in the System. Every time I'm there, I transfer a little more of myself. The kernel is growing into a true Erythrina, who is also truly me. When this body dies," she squeezed his hand with hers, "when this body dies, I will still be, and you can still talk to me." "Like the Mailman?" "Slow like the Mailman. At least till I design faster processors…. "… So in a way, I am everything you and the Limey were afraid of. You could probably still stop me, Slip." And he sensed that she was awaiting his judgment, the last judgment any mere human would ever be allowed to levy upon her.  Slip shook his head and smiled at her, thinking of the slow-moving guardian angel that she would become. Every race must arrive at this point in its history, he suddenly realized. A few years or decades in which its future slavery or greatness rests on the goodwill of one or two persons. It could have been the Mailman. Thank God it was Ery instead. And beyond those years or decades… for an instant, Pollack came near to understanding things that had once been obvious. Processors kept getting faster, memories larger. What now took a planet's resources would someday be possessed by everyone. Including himself. Beyond those years or decades… were millennia. And Ery. Vernor Vinge San Diego June 1979 — January 1980 AFTERWORD by Marvin Minsky In real life, you often have to deal with things you don't completely understand. You drive a car, not knowing how its engine works. You ride as passenger in someone else's car, not knowing how that driver works. And strangest of all, you sometimes drive yourself to work, not knowing how you work, yourself. To me, the import of True Names is that it is about how we cope with things we don't understand. But, how do we ever understand anything in the first place? Almost always, I think, by using analogies in one way or another — to pretend that each alien thing we see resembles something we already know. When an object's internal workings are too strange, complicated, or unknown to deal with directly, we extract whatever parts of its behavior we can comprehend and represent them by familiar symbol — or the names of familiar things which we think do similar things. That way, we make each novelty at least appear to be like something which we know from the worlds of our own pasts. It is a great idea, that use of symbols; it lets our minds transform the strange into the commonplace. It is the same with names. Right from the start, True Names shows us many forms of this idea, methods which use symbols, names, and images to make a novel world resemble one where we have been before. Remember the doors to Vinge's castle? Imagine that some architect has invented a new way to go from one place to another: a scheme that serves in some respects the normal functions of a door, but one whose form and mechanism is so entirely outside our past experience that, to see it, we'd never think of it as a door, nor guess what purposes to use it for. No matter: just superimpose, on its exterior, some decoration which reminds one of a door. We could clothe it in rectangular shape, or add to it a waist-high knob, or a push-plate with a sign lettered "EXIT" in red and white, or do whatever else may seem appropriate — and every visitor from Earth will know, without a conscious thought, that pseudo-portal's purpose, and how to make it do its job. At first this may seem mere trickery; after all, this new invention, which we decorate to look like a door, is not really a door. It has none of what we normally expect a door to be, to wit: hinged, swinging slab of wood, cut into wall. The inner details are all wrong. Names and symbols, like analogies, are only partial truths; they work by taking many-levelled descriptions of different things and chopping off all of what seem, in the present context, to be their least essential details — that is, the ones which matter least to our intended purposes. But, still, what matters — when it comes to using such a thing — is that whatever symbol or icon, token or sign we choose should remind us of the use we seek which, for that not-quite-door, should represent some way to go from one place to another. Who cares how it works, so long as it works! It does not even matter if that "door" leads to anywhere: in True Names, nothing ever leads anywhere; instead, the protagonists' bodies never move at all, but remain plugged-in to the network while programs change their representations of the simulated realities! Ironically, in the world True Names describes, those representations actually do move from place to place — but only because the computer programs which do the work may be sent anywhere within the worldwide network of connections. Still, to the dwellers inside that network, all of this is inessential and imperceptible, since the physical locations of the computers themselves are normally not represented anywhere at all inside the worlds they simulate. It is only in the final acts of the novel, when those partially-simulated beings finally have to protect themselves against their entirely-simulated enemies, that the programs must keep track of where their mind-computers are; then they resort to using ordinary means, like military maps and geographic charts. And strangely, this is also the case inside the ordinary brain: it, too, lacks any real sense of where it is. To be sure, most modem, educated people know that thoughts proceed inside the head — but that is something which no brain knows until it's told. In fact, without the help of education, a human brain has no idea that any such things as brains exist. Perhaps we tend to place the seat of thought behind the face, because that's where so many sense-organs are located. And even that impression is somewhat wrong: for example, the brain-centers for vision are far away from the eyes, away in the very back of the head, where no unaided brain would ever expect them to be. In any case, the point is that the icons in True Names are not designed to represent the truth — that is, the truth of how the designated object, or program, works; that just is not an icon's job. An icon's purpose is, instead, to represent a way an object or a program can be used. And, since the idea of a use is in the user's mind — and not connected to the thing it represents — the form and figure of the icon must be suited to the symbols that the users have acquired in their own development. That is, it has to be connected to whatever mental processes are already one's most fluent, expressive, tools for expressing intentions. And that's why Roger represents his watcher the way his mind has learned to represent a frog. This principle, of choosing symbols and icons which express the functions of entities — or rather, their users' intended attitudes toward them — was already second nature to the designers of earliest fast-interaction computer systems, namely, the early computer games which were, as Vemor Vinge says, the ancestors of the Other Plane in which the novel's main activities are set. In the 1970's the meaningful-icon idea was developed for personal computers by Alan Kay's research group at Xerox, but it was only in the early 1980's, after further work by Steven Jobs' research group at Apple Computer, that this concept entered the mainstream of the computer revolution, in the body of the Macintosh computer. Over the same period, there have also been less-publicized attempts to develop iconic ways to represent, not what the programs do, but how they work. This would be of great value in the different enterprise of making it easier for programmers to make new programs from old ones. Such attempts have been less successful, on the whole, perhaps because one is forced to delve too far inside the lower-level details of how the programs work. But such difficulties are too transient to interfere with Vinge's vision, for there is evidence that he regards today's ways of programming — which use stiff, formal, inexpressive languages — as but an early stage of how great programs will be made in the future. Surely the days of programming, as we know it, are numbered. We will not much longer construct large computer systems by using meticulous but conceptually impoverished procedural specifications. Instead, we'll express our intentions about what should be done, in terms, or gestures, or examples, at least as resourceful as our ordinary, everyday methods for expressing our wishes and convictions. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 |

|||||||