|

|

Популярные авторы:: Раззаков Федор :: Горький Максим :: Грин Александр :: Борхес Хорхе Луис :: Азимов Айзек :: Лесков Николай Семёнович :: Толстой Лев Николаевич :: Чехов Антон Павлович :: Кларк Артур Чарльз :: Картленд Барбара Популярные книги:: Дюна (Книги 1-3) :: Справочник по реестру Windows XP :: Паштет из гусиной печенки :: Цена риска [Риск] :: Мнимые величины :: Жизнь Клима Самгина (Часть 4) :: Краткое содержание произведений русской литературы I половины XX века :: An Encounter :: The Boarding House :: Летняя ночь |

True NamesModernLib.Net / Научная фантастика / Vinge Vernor / True Names - Чтение (стр. 3)

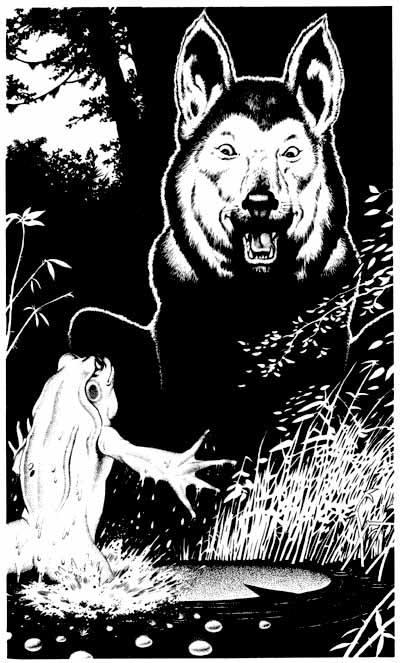

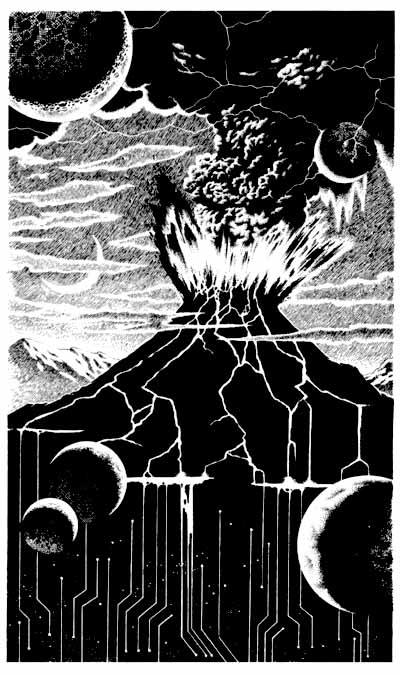

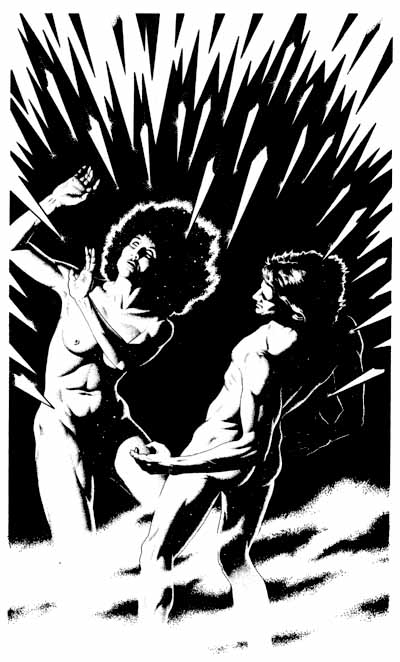

"Just a little bit farther," Erythrina said over her shoulder, speaking in the beast language (encipherment) that they had chosen with their forms. Minutes later, they shrank into the brush, out of the way of two armored hackers that proceeded implacably up the trail. The pair drove in single file, the impossibly large eight-cylinder engines on their bikes belching fire and smoke and noise. The one bringing up the rear carried an old-style recoilless rifle decorated with swastikas and chrome. Dim fires glowed through their blackened face plates. The two dogs eyed the bikers timidly, as befitted their present disguise, but Mr. Slippery had the feeling he was looking at a couple of amateurs who were imaging beyond their station in life: the bikes' tires didn't always touch the ground, and the tracks they left didn't quite match the texture of the muck. Anyone could put on a heroic image in this plane, or appear as some dreadful monster. The problem was that there were always skilled users who were willing to cut such pretenders down to size — perhaps even to destroy their access. It befitted the less experienced to appear small and inconspicuous, and to stay out of others' way. (Mr. Slippery had often speculated just how the simple notion of using high-resolution EEGs as input/output devices had caused the development of the "magical world" representation of data space. The Limey and Erythrina argued that sprites, reincarnation, spells, and castles were the natural tools here, more natural than the atomistic twentieth-century notions of data structures, programs, files, and communications protocols. It was, they argued, just more convenient for the mind to use the global ideas of magic as the tokens to manipulate this new environment. They had a point; in fact, it was likely that the governments of the world hadn't caught up to the skills of the better warlocks simply because they refused to indulge in the foolish imaginings of fantasy. Mr. Slippery looked down at the reflection in the pool beside him and saw the huge canine face and lolling tongue looking up at him; he winked at the image. He knew that despite all his friends' high intellectual arguments, there was another reason for the present state of affairs, a reason that went back to the Moon Lander and Adventure games at the "dawn of time": it was simply a hell of a lot of fun to live in a world as malleable as the human imagination.) Once the riders were out of sight, Erythrina moved back across the path to the edge of the pond and peered long and hard down between the lilies, into the limpid depths. "Okay, let's do some cross-correlation. You take the JPL data base, and I'll take the Harvard Multispectral Patrol. Start with data coming off space probes out to ten AUs. I have a suspicion the easiest way for the Mailman to disguise his transmissions is to play trojan horse with data from a NASA spacecraft." Mr. Slippery nodded. One way or another, they should resolve her alien invasion theory first. "It should take me about half an hour to get in place. After that, we can set up for the correlation. Hmmm … if something goes wrong, let's agree to meet at Mass Transmit 3," and she gave a password scheme. Clearly that would be an emergency situation. If they weren't back in the castle within three or four hours, the others would certainly guess the existence of her secret exit. Erythrina tensed, then dived into the water. There was a small splash, and the lilies bobbed gently in the expanding ring waves. Mr. Slippery looked deep, but as expected, there was no further sign of her. He padded around the side of the pool, trying to identify the special glow of the JPL data base. There was thrashing near one of the larger lilies, one that he recognized as obscuring the NSA connections with the East/West net. A large bullfrog scrambled out of the water onto the pad and turned to look at him. "Aha! Gotcha, you sonofabitch!"  It was Virginia; the voice was the same, even if the body was different. " Shhhhhh! " said Mr. Slippery, and looked wildly about for signs of eavesdroppers. There were none, but that did not mean they were safe. He spread his best privacy spell over her and crawled to the point closest to the lily. They sat glaring at each other like some characters out of La Fontaine: The Tale of the Frog and Dog. How dearly he would love to leap across the water and bite off that fat little head. Unfortunately the victory would be a bit temporary. "How did you find me?" Mr. Slippery growled. If people as inexperienced as the Feds could trace him down in his disguise, he was hardly safe from the Mailman. "You forget," the frog puffed smugly. "We know your Name. It's simple to monitor your home processor and follow your every move." Mr. Slippery whined deep in his throat. In thrall to a frog. Even Wiley has done better than that . "Okay, so you found me. Now what do you want?" "To let you know that we want results, and to get a progress report." He lowered his muzzle till his eyes were even with Virginia's. "Heh heh. I'll give you a progress report, but you're not going to like it." And he proceeded to explain Erythrina's theory that the Mailman was an alien invasion. "Rubbish," spoke the frog afterward. "Sheer fantasy! You're going to have to do better than that, Pol er, Mister." He shuddered. She had almost spoken his Name. Was that a calculated threat or was she simply as stupid as she seemed? Nevertheless, he persisted. "Well then, what about Venezuela?" He related the evidence Ery had that the coup in that country was the Mailman's work. This time the frog did not reply. Its eyes glazed over with apparent shock, and he realized that Virginia must be consulting people at the other end. Almost fifteen minutes passed. When the frog's eyes cleared, it was much more subdued. "We'll check on that one. What you say is possible. Just barely possible. If true… well, if it's true, this is the biggest threat we've had to face this century." And you see that I am perhaps the only one who can bail you out . Mr. Slippery relaxed slightly. If they only realized it, they were thralled to him as much as the reverse — at least for the moment. Then he remembered Erythrina's plan to grab as much power as they could for a brief time and try to use that advantage to flush the Mailman out. With the Feds on their side, they could do more than Ery had ever imagined. He said as much to Virginia. The frog croaked, " You … want … us … to give you carte blanche in the Federal data system? Maybe you'd like to be President and Chair of the JCS, to boot?" "Hey, that's not what I said. I know it's an extraordinary suggestion, but this is an extraordinary situation. And in any case, you know my Name. There's no way I can get around that." The frog went glassy-eyed again, but this time for only a couple of minutes. "We'll get back to you on that. We've got a lot of checking to do on the rest of your theories before we commit ourselves to anything. Till further notice, though, you're grounded." "Wait!" What would Ery do when he didn't show? If he wasn't back in the castle in three or four hours, the others would surely know about the secret exit. The frog was implacable. "I said, you're grounded, Mister. We want you back in the real world immediately. And you'll stay grounded till you hear from us. Got it?" The dog slumped. "Yeah." "Okay." The frog clambered heavily to the edge of the sagging lily and dumped itself ungracefully into the water. After a few seconds, Mr. Slippery followed. Coming back was much like waking from a deep daydream; only here it was the middle of the night. Roger Pollack stood, stretching, trying to get the kinks out of his muscles. Almost four hours he had been gone, longer than ever before. Normally his concentration began to fail after two or three hours. Since he didn't like the thought of drugging up, this put a definite limit on his endurance in the Other Plane. Beyond the bungalow's picture window, the pines stood silhouetted against the Milky Way. He cranked open a pane and listened to the night birds trilling out there in the trees. It was near the end of spring; he liked to imagine he could see dim polar twilight to the north. More likely it was just Crescent City. Pollack' leaned close to the window and looked high into the sky, where Mars sat close to Jupiter. It was hard to think of a threat to his own life from as far away as that. Pollack backed up the spells acquired during this last session, powered down his system, and stumbled off to bed. The following morning and afternoon seemed the longest of Roger Pollack's life. How would they get in touch with him? Another visit of goons and black Lincolns? What had Erythrina done when he didn't make contact? Was she all right? And there was just no way of checking. He paced back and forth across his tiny living room, the novel — plots that were his normal work forgotten. Ah, but there is a way . He looked at his old data set with dawning recognition. Virginia had said to stay out of the Other Plane. But how could they object to his using a simple data set, no more efficient than millions used by office workers all over the world? He sat down at the set, scraped the dust from the handpads and screen. He awkwardly entered long-unused call symbols and watched the flow of news across the screen. A few queries and he discovered that no great disasters had occurred overnight, that the insurgency in Indonesia seemed temporarily abated. (Wiley J. was not to be king just yet.) There were no reports of big-time data vandals biting the dust. Pollack grunted. He had forgotten how tedious it was to see the world through a data set, even with audio entry. In the Other Plane, he could pick up this sort of information in seconds, as casually as an ordinary mortal might glance out the window to see if it is raining. He dumped the last twenty-four hours of the world bulletin board into his home memory space and began checking through it. The bulletin board was ideal for untraceable reception of messages: any — one on Earth could leave a message — indexed by subject, target audience, and source. If a user copied the entire board, and then searched it, there was no outside record of exactly what information he was interested in. There were also simple ways to make nearly untraceable entries on the board. As usual, there were about a dozen messages for Mr. Slippery. Most of them were from fans; the Coven had greater notoriety than any other vandal SIG. A few were for other Mr. Slipperys. With five billion people in the world, that wasn't surprising. And one of the memos was from the Mailman; that's what it said in the source field. Pollack punched the message up on the screen. It was in caps, with no color or sound. Like all messages directly from the Mailman, it looked as if it came off some incredibly ancient I/O device: YOU COULD HAVE BEEN RICH. YOU COULD HAVE RULED. INSTEAD YOU CONSPIRED AGAINST ME. I KNOW ABOUT THE SECRET EXIT. I KNOW ABOUT YOUR DOGGY DEPARTURE. YOU AND THE RED ONE ARE DEAD NOW. IF YOU EVER SNEAK BACK ONTO THIS PLANE, IT WILL BE THE TRUE DEATH — I AM THAT CLOSE TO KNOWING YOUR NAMES. *****WATCH FOR ME IN THE NEWS, SUCKER********* Bluff, thought Roger. He wouldn't be sending out warnings if he has that kind of power . Still, there was a dropping sensation in his stomach. The Mailman shouldn't have known about the dog disguise. Was he onto Mr. Slippery's connection with the Feds? If so, he might really be able to find Slippery's True Name. And what sort of danger was Ery in? What had she done when he missed the rendezvous at Mass Transmit 3? A quick search showed no messages from Erythrina. Either she was looking for him in the Other Plane, or she was as thoroughly grounded as he. He was still stewing on this when the phone rang. He said, "Accept, no video send." His data set cleared to an even gray: the caller was not sending video either. "You're still there? Good." It was Virginia. Her voice sounded a bit odd, subdued and tense. Perhaps it was just the effect of the scrambling algorithms. He prayed she would not trust that scrambling. He had never bothered to make his phone any more secure than average. (And he had seen the schemes Wiley J. and Robin Hood had devised to decrypt thousands of commercial phone messages in real-time and monitor for key phrases, signaling them when anything interesting was detected. They couldn't use the technique very effectively, since it took an enormous amount of processor space, but the Mailman was probably not so limited.) Virginia continued, "No names, okay? We checked out what you told us and… it looks like you're right. We can't be sure about your theory about his origin, but what you said about the international situation was verified." So the Venezuela coup had been an outside take-over. "Furthermore, we think he has infiltrated us much more than we thought. It may be that the evidence we had of unsuccessful meddling was just a red herring." Pollack recognized the fear in her voice now. Apparently the Feds saw that they were up against something catastrophic. They were caught with their countermeasures down, and their only hope lay with unreliables like Pollack. "Anyway, we're going ahead with what you suggested. We'll provide you two with the resources you requested. We want you in the Other … place as soon as possible. We can talk more there." "I'm on my way. I'll check with my friend and get back to you there." He cut the connection without waiting for a reply. Pollack sat back, trying to savor this triumph and the near-pleading in the cop's voice. Somehow, he couldn't. He knew what a hard case she was; anything that could make her crawl was more hellish than anything he wanted to face. His first stop was Mass Transmit 3. Physically, MT3 was a two-thousand-tonne satellite in synchronous orbit over the Indian Ocean. The Mass Transmits handled most of the planet's noninteractive communications (and in fact that included a lot of transmission that most people regarded as interactive — such as human/human and the simpler human/computer conversations). Bandwidth and processor space was cheaper on the Mass Transmits because of the 240— to 900-millisecond time delays that were involved. As such, it was a nice out-of-the-way meeting place, and in the Other Plane it was represented as a five-meter-wide ledge near the top of a mountain that rose from the forests and swamps that stood for the lower satellite layer and the ground-based nets. In the distance were two similar peaks, clear in pale sky. Mr. Slippery leaned out into the chill breeze that swept the face of the mountain and looked down past the timberline, past the evergreen forests. Through the unnatural mists that blanketed those realms, he thought he could see the Coven's castle. Perhaps he should go there, or down to the swamps. There was no sign of Erythrina. Only sprites in the forms of bats and tiny griffins were to be seen here. They sailed back and forth over him, sometimes soaring far higher, toward the uttermost peak itself. Mr. Slippery himself was in an extravagant winged man form, one that subtly projected amateurism, one that he hoped would pass the inspection of the enemy's eyes and ears. He fluttered clumsily across the ledge toward a small cave that provided some shelter from the whistling wind. Fine, wind-dropped snow lay in a small bank before the entrance. The insects he found in the cave were no more than what they seemed-amateur transponders. He turned and started back toward the drop-off; he was going to have to face this alone. But as he passed the snowbank, the wind swirled it up and tiny crystals stung his face and hands and nose. Trap! He jumped backward, his fastest escape spell coming to his lips, at the same time cursing himself for not establishing the spell before. The time delay was just too long; the trap lived here at MT3 and could react faster than he. The little snow-devil dragged the crystals up into a swirling column of singing motes that chimed in near-unison, "W-w-wait-t-t!" The sound matched deep-set recognition patterns; this was Erythrina's work. Three hundred milliseconds passed, and the wind suddenly picked up the rest of the snow and whirled into a more substantial, taller column. Mr. Slippery realized that the trap had been more of an alarm, set to bring Ery if he should be recognized here. But her arrival was so quick that she must already have been at work somewhere in this plane. "Where have you been-n-n!" The snow-devil's chime was a combination of rage and concern. Mr. Slippery threw a second spell over the one he recognized she had cast. There was no help for it: he would have to tell her that the Feds had his Name. And with that news, Virginia's confirmation about Venezuela and the Feds' offer to help. Erythrina didn't respond immediately — and only part of the delay was light lag. Then the swirling snow flecks that represented her gusted up around him. "So you lose no matter how this comes out, eh? I'm sorry, Slip." Mr. Slippery's wings drooped. "Yeah. But I'm beginning to believe it will be the True Death for us all if we don't stop the Mailman. He really means to take over … everything. Can you imagine what it would be like if all the governments' wee megalomaniacs got replaced by one big one?" The usual pause. The snow-devil seemed to shudder in on itself. "You're right; we've got to stop him even if it means working for Sammy Sugar and the entire DoW." She chuckled, a near-inaudible chiming. "Even if it means that they have to work for us ." She could laugh; the Feds didn't know her Name. "How did your Federal Friends say we could plug into their system?" Her form was changing again — to a solid, winged form, an albino eagle. The only red she allowed herself was in the eyes, which gleamed with inner light. "At the Laurel end of the old arpa net. We'll get something near carte blanche on that and on the DoJ domestic intelligence files, but we have to enter through one physical location and with just the password scheme they specify." He and Erythrina would have more power than any vandals in history, but they would be on a short leash, nevertheless. His wings beat briefly, and he rose into the air. After the usual pause, the eagle followed. They flew almost to the mountain's peak, then began the long, slow glide toward the marshes below, the chill air whistling around them. In principle, they could have made the transfer to the Laurel terminus virtually instantaneously. But it was not mere romanticism that made them move so cautiously — as many a novice had discovered the hard way. What appeared to the conscious mind as a search for air currents and clear lanes through the scattered clouds was a manifestation of the almost-subconscious working of programs that gradually transferred processing from rented space on MT3 to low satellite and ground-based stations. The game was tricky and time-consuming, but it made it virtually impossible for others to trace their origin. The greatest danger of detection would probably occur at Laurel, where they would be forced to access the system through a single input device. The sky glowed momentarily; seconds passed, and an airborne fist slammed into them from behind. The shock wave sent them tumbling taft over wing toward the forests below. Mr. Slippery straightened his chaotic flailing into a head-first dive. Looking back which was easy to do in his present attitude he saw the peak that had been MT3 glowing red, steam rising over descending avalanches of lava. Even at this distance, he could see tiny motes swirling above the inferno. (Attackers looking for the prey that had fled?) Had it come just a few seconds earlier, they would have had most of their processing still locked into MT3 and the disaster — whatever it really was — would have knocked them out of this plane. It wouldn't have been the True Death, but it might well have grounded them for days.  On his right, he glimpsed the white eagle in a controlled dive; they had had just enough communications established off MT3 to survive. As they fell deeper into the humid air of the lowlands, Mr. Slippery dipped into the news channels: word was already coming over the LA Times of the fluke accident in which the Hokkaido aerospace launching laser had somehow shone on MT3's optics. The laser had shone for microseconds and at reduced power; the damage had been nothing like a Finger of God, say. No one had been hurt, but wideband communications would be down. for some time, and several hundred million dollars of information traffic was stalled. There would be investigations and a lot of very irate customers. It had been no accident, Mr. Slippery was sure. The Mailman was showing his teeth, revealing infiltration no one had suspected. He must guess what his opponents were up to. They leveled out a dozen meters above the pine forest that bordered the swamps. The air around them was thick and humid, and the faraway mountains were almost invisible. Clouds had moved in, and a storm was on the way. They were now securely locked into the low-level satellite net, but thousands of new users were clamoring for entry, too. The loss of MT3 would make the Other Plane a turbulent place for several weeks, as heavy users tried to shift their traffic here. He swooped low over the swamp, searching for the one particular pond with the one particularly large water lily that marked the only entrance Virginia would permit them. There! He banked off to the side, Erythrina following, and looked for signs of the Mailman or his friends in the mucky clearings that surrounded the pond. But there was little purpose in further caution. Flying about like this, they would be clearly visible to any ambushers waiting by the pond. Better to move fast now that we're committed . He signaled the red-eyed eagle, and they dived toward the placid water. That surface marked the symbolic transition to observation mode. No longer was he aware of a winged form or of water coming up and around him. Now he was interacting directly with the I/O protocols of a computing center in the vicinity of Laurel, Maryland. He sensed Ery poking around on her own. This wasn't the arpa entrance. He slipped "sideways" into an old-fashioned government office complex. The "feel" of the 1990-style data sets was unmistakable. He was fleetingly aware of memos written and edited, reports hauled in and out of storage. One of the vandals' favorite sports and one that even the moderately skilled could indulge in — was to infiltrate one of these office complexes and simulate higher level input to make absurd and impossible demands on the local staff. This was not the time for such games, and this was still not the entrance. He pulled away from the office complex and searched through some old directories. Arpa went back more than half a century, the first of the serious data nets, now (figuratively) gathering dust. The number was still there, though. He signaled Erythrina, and the two of them presented themselves at the log-in point and provided just the codes that Virginia had given him. … and they were in. They eagerly soaked in the megabytes of password keys and access data that Virginia's people had left there. At the same time, they were aware that this activity was being monitored. The Feds were taking an immense chance leaving this material here, and they were going to do their best to keep a rein on their temporary vandal allies. In fifteen seconds, they had learned more about the inner workings of the Justice Department and DoW than the Coven had in fifteen months. Mr. Slippery guessed that Erythrina must be busy plotting what she would do with all that data later on. For him, of course, there was no future in it. They drifted out of the arpa "vault" into the larger data spaces that were the Department of Justice files. He could see that there was nothing hidden from them; random archive retrievals were all being honored and with a speed that would have made deception impossible. They had subpoena power and clearances and more. "Let's go get 'im, Slip." Erythrina's voice seemed hollow and inhuman in this underimaged realm. (How long would it be before the Feds started to make their data perceivable analogically, as on the Other Plane? It might be a little undignified, but it would revolutionize their operation — which, from the Coven's standpoint, might be quite a bad thing.) Mr. Slippery "nodded." Now they had more than enough power to undertake the sort of work they had planned. In seconds, they had searched all the locally available files on off-planet transmissions. Then they dove out of the DoJ net, Mr. Slippery to Pasadena and the JPL planetary probe archives, Erythrina to Cambridge and the Harvard Multispectral Patrol. It should take several hours to survey these records, to determine just what transmissions might be cover for the alien invasion that both the Feds and Erythrina were guessing had begun. But Mr. Slippery had barely started when he noticed that there were dozens of processors within reach that he could just grab with his new Federal powers. He checked carefully to make sure he wasn't upsetting air traffic control or hospital life support, then quietly stole the computing resources of several hundred unknowing users, whose data sets automatically switched to other resources. Now he had more power than he ever would have risked taking in the past. On the other side of the continent, he was aware that Erythrina had done something similar. In three minutes, they had sifted through five years' transmissions far more thoroughly than they had originally planned. "No sign of him," he sighed and "looked" at Erythrina. They had found plenty of irregular sources at Harvard, but there was no orbital fit. All transmissions from the NASA probes checked out legitimately. "Yes." Her face, with its dark skin and slanting eyes, seemed to hover beside him. Apparently with her new power, she could image even here. "But you know, we haven't really done much more than the Feds could — given a couple months of data set work …. I know, it's more than we had planned to do. But we've barely used the resources they've opened to us." It was true. He looked around, feeling suddenly like a small boy let loose in a candy shop: he sensed enormous data bases and the power that would let him use them. Perhaps the cops had not intended them to take advantage of this, but it was obvious that with these powers, they could do a search no enemy could evade. "Okay," he said finally, "let's pig it." Ery laughed and made a loud snuffling sound. Carefully, quickly, they grabbed noncritical data— processing facilities along all the East/West nets. In seconds, they were the biggest users in North America. The drain would be clear to anyone monitoring the System, though a casual user might notice only increased delays in turnaround. Modem nets are at least as resilient as old-time power nets — but like power nets, they have their elastic limit and their breaking point. So far, at least, he and Erythrina were far short of those. — but they were experiencing what no human had ever known before, a sensory bandwidth thousands of times normal. For seconds that seemed without end, their minds were filled with a jumble verging on pain, data that was not information and information that was not knowledge. To hear ten million simultaneous phone conversations, to see the continent's entire video output, should have been a white noise. Instead it was a tidal wave of detail rammed through the tiny aperture of their minds. The pain increased, and Mr. Slippery panicked. This could be the True Death, some kind of sensory burnout —  Erythrina's voice was faint against the roar, " Use everything, not just the inputs! " And he had just enough sense left to see what she meant. He controlled more than raw data now; if he could master them, the continent's computers could process this avalanche, much the way parts of the human brain preprocess their input. More seconds passed, but now with a sense of time, as he struggled to distribute his very consciousness through the System. Then it was over, and he had control once more. But things would never be the same: the human that had been Mr. Slippery was an insect wandering in the cathedral his mind had become. There simply was more there than before. No sparrow could fall without his knowledge, via air traffic control; no check could be cashed without his noticing over the bank communication net. More than three hundred million lives swept before what his senses had become. Around and through him, he felt the other occupant — Erythrina, now equally grown. They looked at each other for an unending fraction of a second, their communication more kinesthetic than verbal. Finally she smiled, the old smile now deep with meanings she could never image before. "Pity the poor Mailman now!" Again they searched, but now it was through all the civil data bases, a search that could only be dreamed of by mortals. The signs were there, a near invisible system of manipulations hidden among more routine crimes and vandalisms. Someone had been at work within the Venezuelan system, at least at the North American end. The trail was tricky to follow — their enemy seemed to have at least some of their own powers — but they saw it lead back into the labyrinths of the Federal bureaucracy: resources diverted, individuals promoted or transferred, not quite according to the automatic regulations that should govern. These were changes so small they were never guessed at by ordinary employees and only just sensed by the cops. But over the months, they added up to an instability that neither of the two searchers could quite understand except to know that it was planned and that it did the status quo no good. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 |

|||||||